Access to education

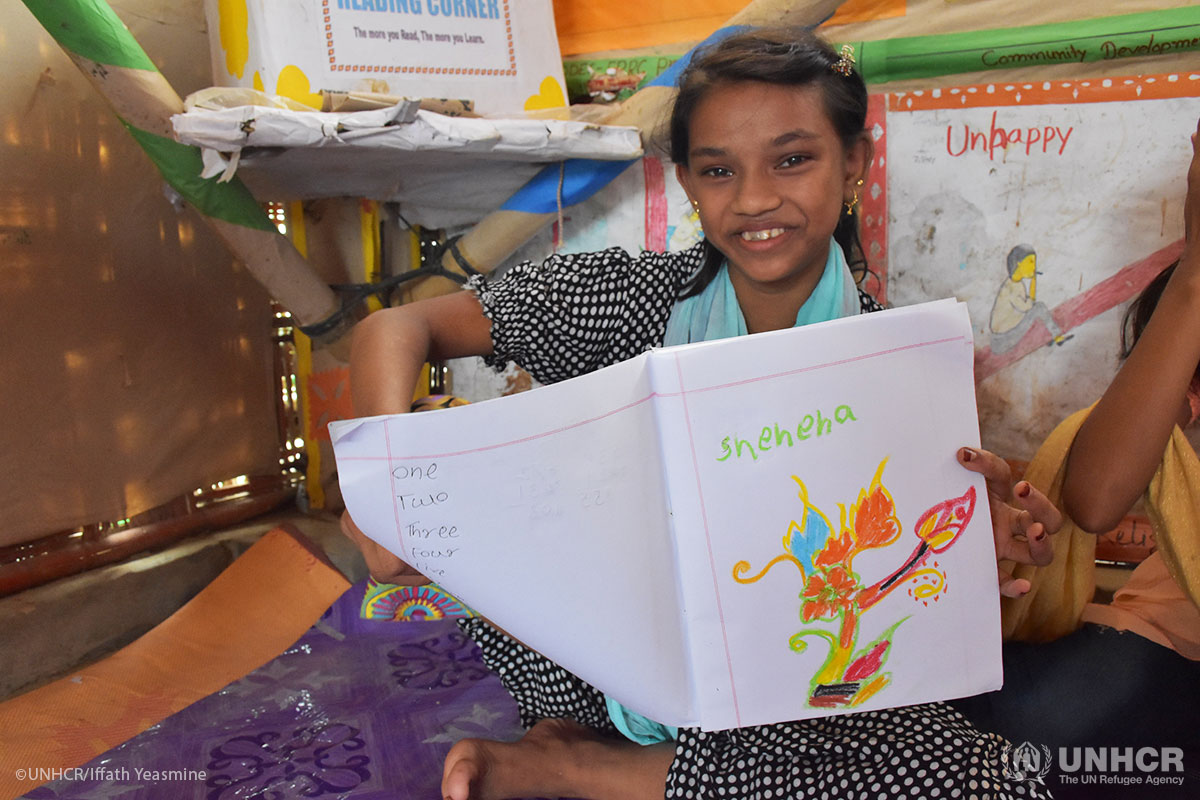

They don’t have desks or chairs. But in a bamboo hut decorated with posters and paintings, 30 Rohingya teenage girls are sitting on the ground, laser-focused on the day’s math lesson.

The makeshift classroom, known as the Diamond Adolescent Club, was established two years ago in the Kutupalong refugee camp — our world’s largest — in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. It is run by a local partner of UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, and supported by generous Americans.

One of the students is Shehana, 16. She and her family are among nearly 750,000 refugees who fled a violent military crackdown and ethnic cleansing campaign in Myanmar. Back home, she loved going to school and had big plans: “I wanted to be a teacher and to be able to go to college. I love teaching.”

Shehana is happy to attend classes in Kutupalong and recognizes the value of education: “We learn new things almost every day. I try to tell others why education is important and to convince them to let girls study — how it can help with better opportunities in the future.” And her advocacy has been successful: “Some of our relatives have listened to me and they now send their daughters to school.”

Shehana’s brother, Mohammed Sharif, 17, also studies at the Diamond Adolescent Club. One of her sisters, 21-year-old Jannat Ara, teaches young children at another learning center, bringing along her own 5-year-old daughter.

The source of this family’s commitment to education is their father, Nul Alam. He was the headmaster of a 450-student school in Maungdaw, a town in western Myanmar. Mr. Alam was one of a few Rohingya appointed to a senior position in that country, where his people have suffered discrimination, persecution, violence and other human rights abuses for generations.

Today, Mr. Alam teaches as a volunteer at a mosque in Kutupalong, but it’s clear that he misses his students back home. Showing a photo of them on his phone, he said: “I feel like crying when I see this. I miss my students very much. Many of my old students who completed are in the camp here. Many have positions as volunteers working with organizations in the camp … when they see me, they greet me.”

More than half of all Rohingya refugees are under 18. Without education, they risk becoming a lost generation, which is why UNHCR is working to ensure that students like Shehana, her brother and her sister can go to school. As Filippo Grandi, UN High Commissioner for Refugees, says: “Children in school are less likely to be involved in child labor or criminal activity, or to come under the influence of gangs and militias. Girls are less likely to be coerced into early marriage and pregnancy, and can study and socialize in safe spaces.”

Here’s how you can help

3.7 million refugee children are out of school. By supporting their education, you are investing in them — and in humanity. Please make a brighter future possible for others like Shehana by becoming USA for UNHCR’s newest monthly donor today.