‘I believe we can make change happen. We just need to do the work.’

In his new memoir, ‘Asylum,’ Nigerian refugee and LGBTIQ+ activist Edafe Okporo writes that even detention and discrimination didn’t shake his faith in America.

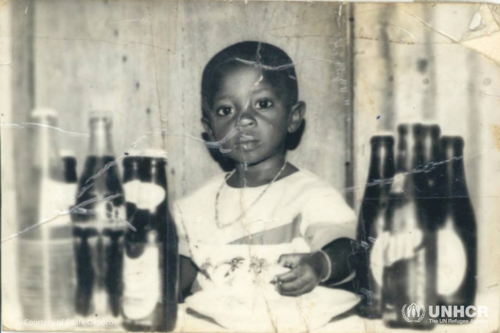

In 2016, while at his office in Abuja, Nigeria, Edafe Okporo received a text message from a friend containing a link to an article announcing Edafe had won an award from a U.S.-based nonprofit for his advocacy on behalf of gay men. The news was a surprise – and a death sentence.

As a gay man in Nigeria, Edafe had already survived numerous attacks and discrimination – an angry mob once beat him chanting, “Gay! Gay! Gay!” He had moved several times around the country. With this new publicity, he could no longer keep a low profile. It was only a matter of time, he knew, before someone turned him into the police in the name of the country’s strict laws against homosexuality, or worse.

“What should have been a proud moment quickly turned dark,” he writes in his memoir, Asylum (Simon & Schuster 2022), released last week. “This single blazing moment brought my life in Nigeria to an end. I had to run – the farther the better.”

Edafe received asylum in the United States, but only after spending more than five months in an immigration detention center, locked away with other people who, like him, hoped to start over in America. They slept on concrete slabs, rarely saw sunlight and when sick, were lucky to even see a doctor.

“Just let our stories be added to that American narrative.”

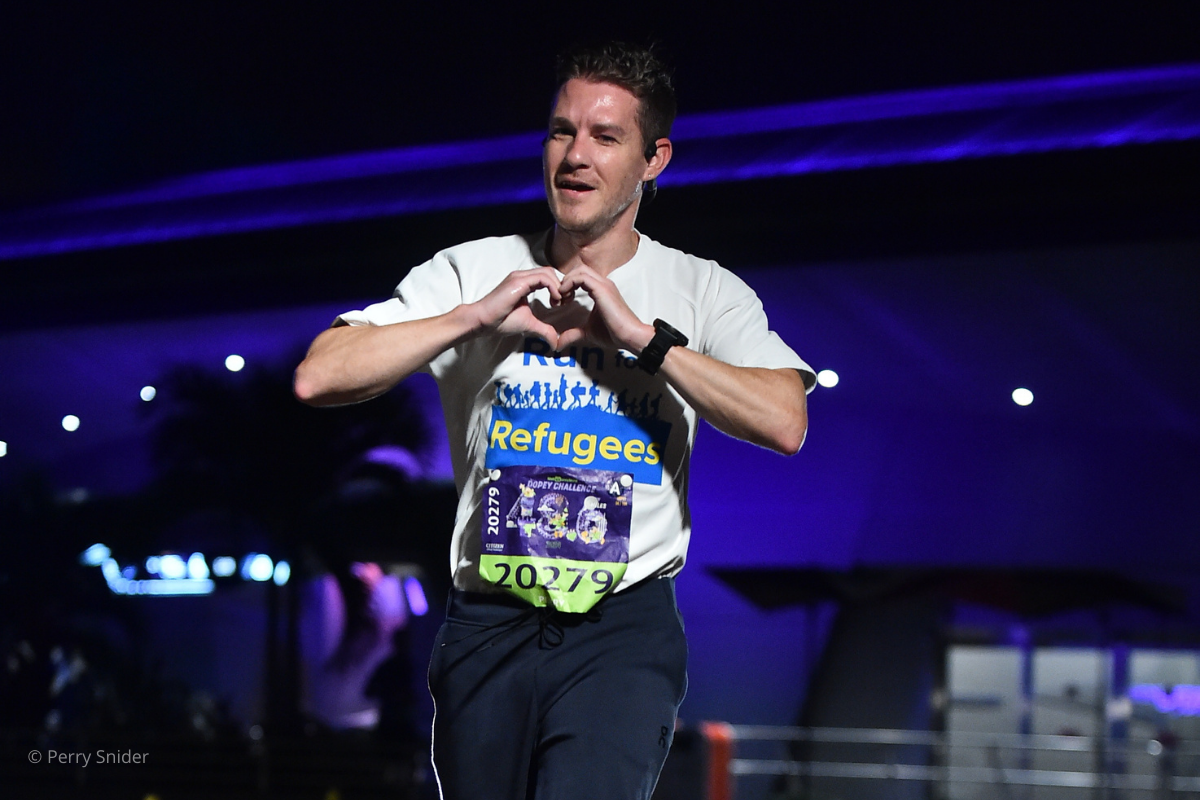

Now, Edafe lives in New York with his partner, whom he plans to marry this summer. He has won more awards, including one for his work as the director of a homeless shelter, RDJ Refugee Shelter, for people seeking asylum. He recently founded a nonprofit, Refugee America, to help other LGBTIQ+ refugees. And, he has become a sought after writer and speaker on the experiences of LGBTIQ+ refugees.

Edafe sat down with UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, to talk about his new memoir, how the U.S. and other countries can welcome refugees and why this month – Pride Month in the U.S. – feels like a celebration of his personal journey.

The interview below has been edited for length and clarity.

In the last part of your book, you ask people to think about what kind of a country do they want to be in. You said that question motivates you in your work.

Yeah, I think that that is the most important question. The U.S. has been a country of refuge, not just for refugees, but for millions of people who have a dream and a goal – to find a life for themselves. It's just that right now, the [political] polarization in America makes it difficult for us to be human and to be empathetic. I think that this is the America I want to live in, but just a more empathetic. America is still one of the best places you could go to as a displaced person. It's multi dimensional, it’s very diverse. There is no [other] place on Earth I could have come five years ago and in five years time have a master's degree, be engaged to be married, and have a roof over my head. America presented me the opportunity to build a life. And this is the America I want. Just let our stories [of displaced people] be added to that American narrative.

People want you to be either on the far right or the far left [of the political spectrum]. If you are not polarized, you don’t get the audience of Americans because people want to listen to those who adhere to their opinions. The country I want to be in is the country that has a middle ground for both right and left voices to be heard.

So how do you position yourself as a writer and activist, and actually even as a person, as someone living here? In a country where there isn’t that middle road, how do you forge it?

I think about this question all the time. Like, do I get more polarized just to get my voice heard? And I say to myself that if everybody moves into the right or the left because they want their voices to be heard, the middle gets thinner, thinner and thinner and almost becomes invisible. I prefer not to be heard and to be in the middle of the road than to add polarization to the equation.

I don’t attack any individual. I steer clear from that. I came in under the [Barack] Obama administration, then I gained asylum under the [Donald] Trump administration. And as I was writing my book, I made it clear that both the Democratic and Republican presidents have affected the lives of refugees drastically. As a writer and as an activist, my hope is that one day I could live in a world whereby people who will come after me would have a voice and would not have to struggle for their voices to be heard because I have done some of the work. An activist is not just fighting to change the system, it’s fighting to make people part of the system change. I don’t want to be antagonizing anybody. I want to leave grace for people.

“The country I want to be in is the country that has a middle ground for both right and left voices to be heard.”

One of the things you talk about is making sure that nobody else has to go through [detention]. But do you feel like the U.S. is getting closer to that? Is there any progress?

Yeah. I think that we’re making a lot of progress. So when I came to America, we had the largest mass incarceration of immigrants. Even today, we still have the largest mass incarceration of immigrants in the world. But the state of California has ruled to end private prisons in the use of detention of immigrants, to phase it out by 2028. Where I was detained, New Jersey, they have agreed to phase out the use of private prisons. There’s a movement to end the use of private prisons.

When I was growing up, I dreamt of America – All [punches fist for emphasis] the time.

The Nigerian soccer team won the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta [Georgia, U.S.]. The [Nigerian] people had the U.S. flag in their living rooms. People respect and adore the United States. But to come here and see that this country that I thought to be like heaven treated people like this was really devastating. [For the] people who are coming here to seek protection, it’s just unfair.

Have you talked to your mom yet about your detention? At the time you were writing the book, you hadn’t.

I can’t. I’m afraid. I think that this is the experience many refugees and displaced people have is that we have to keep it a secret back home. If I told [my mom] that I was in a detention center that was like a jail she’d be like, “What crime did you commit?! Are you fine?!” She would freak out. So I try to protect her from my trauma in America.

In your book you talk about the small things that people did that made you feel welcome. You mentioned your lawyer’s smile. What are some of the little things people can do to make people feel welcome?

I think that it is the little things that made more impact than the big things. One of the things that made the most impact on my stay in America was with Sally, the social worker. When I came out of the detention center, I was at the YMCA in Newark [New Jersey]. She has a car. I don’t know how to drive. I don’t know how to take a train. She picked me up and she drove me to Social Security office to get my Social Security [number] because I couldn’t do anything without [it]. She could have dropped me [there]. I know how to spell. I know how to write in English. I could have done it myself. She just sat with me for two hours. You know, we’re talking and moving from line to line. And she said, ‘I know that America can be very difficult for new immigrants.’ And I’m like, I love everything I’m seeing right now! I just came out of five months from being in the detention center. I want to wait in line! But, you know, at the end of the day, I was just thinking about it. She had a lot of things to do, but she just wanted me to feel like I had somebody there.

Somebody gave me a couch to sleep on. Somebody gave me a laptop to apply for a job. Somebody prepared me for my first job interview…helping me one step at a time to get to where I am right now.

So what is your hope for this book? What do you what do you envision happening next?

[The book] is a manifesto, but before you get to the manifesto it’s a memoir. I want people to get to know about the lives of people who come here to seek protection in America. That it’s not just only the persecution that makes up who we are. It’s also the family we leave behind, the food we leave behind, the culture we leave behind to come to this country to build a life for ourselves.

I could write a beautiful story and just get it done. But I wrote it [so that] every issue I discuss, you’d be like, ‘Wow, what action can I take on this particular issue?’ That is the hope I had when I was writing the book.

“I want people to get to know about the lives of people who come here to seek protection...that it’s not just only the persecution that makes up who we are.”

What was the hardest thing about writing the book?

When I was editing the book, I was just realizing all I have gone through to get here and how I never celebrate myself. All I talk about is my pain. I was crying because I was joyful that I went through those things and they didn’t break me down. Many people I know have gone through a quarter of what I’ve gone through and never been able to pick themselves up. So I was flooded with emotion. Leaving my family very young to start my life. I was beaten by a mob. I was in a detention center. I came here [and faced] racism. Like how much can one person take? But I was still able to build a life.

If you had to do it again, would you flee Nigeria and come to the U.S.?

There’s no place on earth I’d rather be than in the United States of America. Simple – even though there are things that are happening that are difficult for us to even grapple with. But in America, there’s a semblance of progress every single day. So I would come to America again in a heartbeat because I love America.

June is [LGBTIQ+] Pride Month. June 19th is Juneteenth [the holiday that commemorates the emancipation of African slaves in America], June 20th is World Refugee Day. Could there be a time where one person could be celebrated as much as I'm being celebrated right now in America [deep laugh]? It is because Americans progress each and every day. And I believe that we can make change happen. We just need to do the work.

Originally reported by UNHCR.