When the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees began work on January 1, 1951, it was given three years to complete its task of helping millions of European refugees left homeless or in exile after the war. At that time, three years was deemed long enough to resolve the refugee problem once and for all, after which — it was expected — UNHCR’s task would be complete.

Today, there are 16.1 million refugees worldwide under UNHCR’s mandate.[1] More than half are children, and six million are of primary and secondary school-going age. The average length of time a refugee spends in exile is about 20 years. Twenty years is more than an entire childhood, and represents a significant portion of a person’s productive working years. Given this sobering picture, it is critical that we think beyond a refugee’s basic survival. Refugees have skills, ideas, hopes and dreams. They face huge risks and challenges, but — as we saw exemplified in the inspiring achievements of the Refugee Olympic Team — they are also tough, resilient and creative, with the energy and drive to shape their own destinies, given the chance.

“It is critical that we think beyond a refugee’s basic survival.”

Making sure that refugees have access to education is at the heart of UNHCR’s mandate to protect the world’s rapidly increasing refugee population, and central to its mission of finding long-term solutions to refugee crises. However, as the number of people forcibly displaced by conflict and violence rises, demand for education naturally grows and the resources in the countries that shelter them are stretched ever thinner.

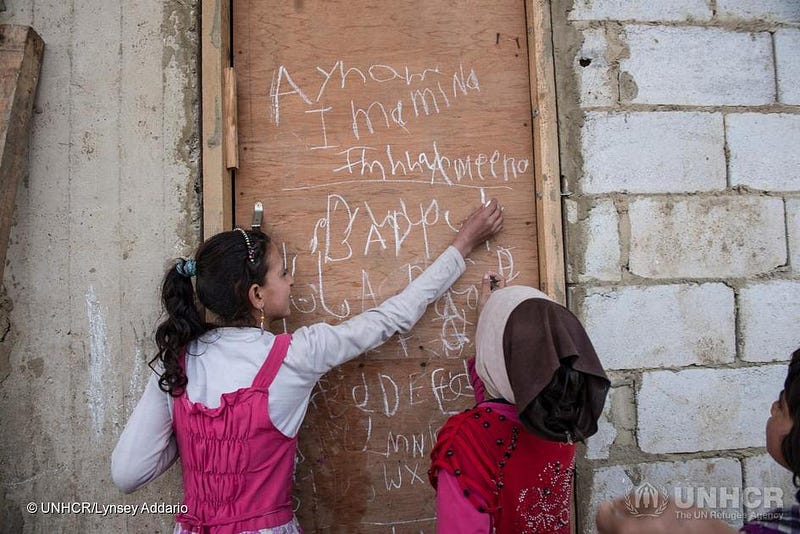

Of the six million primary and secondary school-age refugees under UNHCR’s mandate, 3.7 million have no school to go to. Refugee children are five times more likely to be out of school than non-refugee children. Only 50 per cent have access to primary education, compared with a global level of more than 90 per cent. And as they get older, the gap becomes a chasm: 84 per cent of non-refugee adolescents attend lower secondary school, but only 22 per cent of refugee adolescents have that same opportunity. At the higher education level, just one per cent of refugees attend university compared to 34 per cent globally.[2]

The personal stories in this report show that refugee children and youth — whether they are girls or boys, young children or adolescents, living in cities, towns, camps, or other settlements — regard going to school as a basic need, not a luxury. However, the obstacles to full participation in formal education are considerable.

Esther Nyakong, 18, arrived with her mother and two sisters in Kakuma refugee camp, Kenya, in 2008 unable to speak either English or Swahili. Now she is hoping to beat the hundred to one odds of going to university.

The vast majority of the world’s refugees — 86 per cent — are hosted in developing regions, with more than a quarter in the world’s least developed countries. More than half of the world’s out-of-school refugee children are located in just seven countries: Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Kenya, Lebanon, Pakistan and Turkey. Refugees often live in regions where governments are already struggling to educate their own children. Those governments face the additional task of finding school places, trained teachers and learning materials for tens or even hundreds of thousands of newcomers, who often do not speak the language of instruction and have missed out on an average of three to four years of schooling.

By the end of 2015, 6.7 million refugees were living in protracted situations[3]. Refugees trapped in forced displacement for such long periods find themselves in a state of limbo. Their lives may not be at risk, but their basic rights and essential economic, social and psychological needs can remain unfulfilled. Despite concerted efforts to expand the provision of education to more refugee children and youth, the weight of numbers means that enrolment rates have been falling in the past few years, even in countries where determined efforts have been made to get more refugee children into school.

“Refugee children and youth are not only disadvantaged, but their educational needs and achievements remain largely invisible.”

Although some protracted refugee situations have lasted more than two decades, refugee education is largely financed from emergency funds, leaving little room for long-term planning. Traditionally, refugee education does not feature in national development plans or in education sector planning, but a few of the largest refugee hosting countries are taking steps to correct this.[4]However, refugees’ educational access and attainment are rarely tracked through national monitoring systems, meaning that refugee children and youth are not only disadvantaged, but their educational needs and achievements remain largely invisible.

The returns on investing in education are immense and far-reaching. There is solid evidence that quality education gives children a place of safety and can also reduce child marriage, child labour, exploitative and dangerous work, and teenage pregnancy. It gives them the opportunity to make friends and find mentors, and provides them with the skills for self-reliance, problem solving, critical thinking and teamwork. It improves their job prospects and boosts confidence and self-esteem.

Aletho, 14, is an Ethiopian refugee living in Dadaab camp, Kenya, and dreams of becoming a reporter: “I love imagining things. In real life, I am eagerly waiting to be a journalist.”

Education enables children and youth to thrive, not just survive. Failing to provide education for six million refugees of school-going age, on the other hand, can be hugely damaging, not only for individuals but also for their families and societies, perpetuating cycles of conflict and yet more forced displacement. It means lost opportunities for peaceful and sustainable development in our world. As this report illustrates, education is central to both those goals — peace and development — and to helping refugee children to fulfil their potential.

One year ago, members of the United Nations set out an agenda for global action for the next 15 years. Sustainable Development Goal 4, “Ensure inclusive and quality education for all and promote lifelong learning”, cannot be achieved by 2030 without meeting the education needs of vulnerable populations, including refugees, stateless persons and other forcibly displaced people. The multiplier effect of education on the other goals — on eradicating poverty and hunger, for example, and on promoting gender equality and economic growth — illustrates education’s important role.

“All too often, education for refugee children is considered a luxury, a non-essential optional extra after food, water, shelter and medical care.”

As world leaders gather for the UN General Assembly’s Summit for Refugees and Migrants, and for the Leaders’ Summit on the Global Refugee Crisis hosted by the President of the United States, UNHCR is calling for a broad partnership between government, humanitarian agencies, development partners and the private sector to address the huge gaps in the provision of quality education for all refugees.

We are beginning to acknowledge the scale of the issue. In May this year, governments, companies and philanthropists met at the World Humanitarian Summit in Turkey to create the Education Cannot Wait fund, an initiative to meet the educational needs of millions of children and youth affected by crises around the world.

Hanan Abdel Garbou, 11, a Syrian refugee from Raqqa, gives an impromptu lesson to other children at an informal tented settlement in a former onion factory in Faida, Bekaa valley, Lebanon.

But we are not acting fast enough. All too often, education for refugee children is considered a luxury, a non-essential optional extra after food, water, shelter and medical care. It is the first item to drop off the list when funding is short, as it is today. The figures tell this sorry story: one in two refugee children have access to primary school, which declines to fewer than one in four enrolling in secondary school, dropping to a pitiful one in 100 having the opportunity to continue their studies at university or elsewhere.

This needs to change. By educating tomorrow’s leaders, be they engineers, poets, doctors, scientists, philosophers or computer programmers, we are giving refugees the intellectual tools to shape the future of their own countries from the day they return home, or to contribute meaningfully to the countries that offer them shelter, protection and a vision of a future.

If we neglect this task, we will be failing to nurture peace and prosperity. Education provides the keys to a future in which refugees can find solutions for themselves and their communities.

Refugees face two journeys, one leading to hope, the other to despair. It is up to us to help them along the right path.

UN High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi visits Syrian refugees at a primary school in Beirut, Lebanon.

UN High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi visits Syrian refugees at a primary school in Beirut, Lebanon.